When a young Neil Gaiman first approached Vertigo comics about The Sandman, he was pitching a simple revival of the 70s series of the same name by Joe Simon and Jack “The King” Kirby. But DC editor Karen Berger insisted that while they keep the name, Gaiman should create a new character.

And thank goodness he did, for otherwise the world would have been robbed of something beautiful. Running from 1989 to 1996, for a total 75 issues collected in 10 volumes, The Sandman managed to create its very own expansive self-contained mythology.

The original artists Mike Dringenberg and Sam Kieth fashioned the title character after Gaiman himself. The Sandman, also known as Morpheus or Dream, and by many other names, carries with him an aura of inhumanity. While early issues exist in the DC comic universe with appearances by The Martian Manhunter and John Constantine (hellblazer), the creators quickly realized that Sandman should be a world unto itself, and so that is what it became. Sandman used several different types of stories to keep itself going and to keep it feeling new and alien all the way through to its final issue, but over its run, three types of stories were prevalent.

The Sandman was able to hold on to many overlapping threads throughout its near decade-long run, with characters who appeared in early issues later returning to have their stories told in elaborate detail. This worked well for the first main kind of story that was used. While several volumes are focused on the Sandman himself, there are also a number of stories in which the title character only appears in a minor capacity, and sometimes he fails to appear at all, instead being merely alluded to or referenced by the other characters. These stories were all set in the present and centered on ordinary people who are pulled into problems or adventures that they don’t understand, becoming involved with magic and monsters.

But even when Dream himself didn’t appear, Gaiman never lost focus on what the series was about. Even in these more domestic stories, the focus is on these ordinary people’s dreams, and the effect that dreams can have on the waking world. Whether it be the story of a young woman named Barbie who becomes trapped in her own dreaming, or of a girl named Rose who finds herself with mysterious powers, the underlying idea behind the story is always clear—what is important are the dreams that these characters have, and how these dreams provide a glimpse into the effect that Dream has on the world he inhabits .

The next kind of story that Gaiman used most often involves the various preexisting mythologies that the world has to offer. In The Sandman, the deities from various cultures and mythologies coexist. This allows Dream to engage with different stories from various mythologies, and allows Gaiman to teach the reader about histories and mythologies that they might not have been exposed to otherwise.

The Sandman also includes Biblical figures such as Cain and Able, who in the series exist as servants to Dream in his mystical realm. Cain is doomed to always kill his brother and Able is doomed to be endlessly resurrected. The devil himself is a key figure in several volumes, with Dream actually visiting hell to sort out his conflicts with the infamous fallen angel Lucifer. One such conflict is when Lucifer decides to retire and leaves Dream in charge of hell, leading to all sorts of problems .

Dream also has stories with characters cut from Egyptian mythology, such as the cat god Bast, and characters from Norse mythology, such as Thor, Odin, and Loki, with the latter two becoming important figures in The Sandman’s later volumes. The three Fates from ancient Greek mythology also figure, and in the end they become Dream’s most important foes.

But the third—and probably my personal favorite—kind of narrative that The Sandman employs is historical: the blending of the Sandman’s unique and eerie magic with historical figures and events. This is used to showcase the Kings of Rome and Marco Polo, and, most notably, is used when Morpheus visits the dreams of William Shakespeare, helping to inspire some of the famous playwright’s most beloved works. In issue 19, collected in the third volume Dream Country, Shakespeare’s company puts on A Midsummer Night’s Dream for Morpheus, with actual Fairy Folk sneaking into production. This issue is the only comic book to ever win the World Fantasy Award.My favorite example of this blending of history and fantasy will always be from Volume 6, Fables and Reflections, in which Dream inspires the broken and suicidal Joshua Abraham Norton in the year of 1859 to become the self-proclaimed Emperor of America, a real historical figure who solved social disputes in the city of San Francisco.

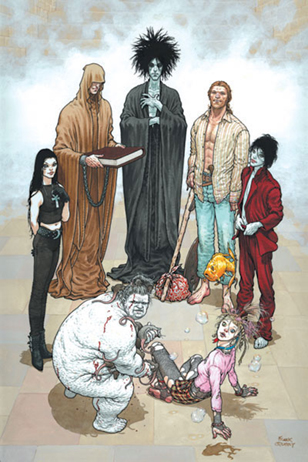

The Sandman is an intelligent, unnerving saga that follows an inhuman, monstrous magical figure. It traces his deeds and misdeeds throughout history with his siblings Destiny, Despair, Desire, Destruction, Delirium, and Death. The Sandman is a unique and beautiful series, and should always be remembered both as one of Gaiman’s crowning achievements and as one of the greatest creations of the comic book medium.

-contributed by Ben Ghan